An Assessment

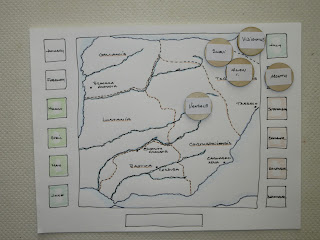

The most important change from the initial test of Sub

Roman Britain to that of Hispania was how best to reconcile the passage of

time. This was solved by changing the value of the card drawn to read the

number of ‘months’ in place of ‘years’. This ensured that key events would have

relevance in the game and not be quickly passed over.

Assigning a suite to represent the principle barbarian

nations was easily done. The fourth suite was reserved for ‘Rome’ and later the

local government officials or senators. The eventual split of the Vandals to the

Asding and Siling was solved using the same suite, but an odd or even card drawn

would allow that tribal group take action.

The cast of one die to determine the attacker/defender

remained as did the method to determine the terrain to be used. In the seven

major engagements, five were fought on arable ground, one in hilly terrain and

one in a forest region.

Battles between full size armies did take place, but

this was rare. The rebellion in Gallicia had six elements per side turned out

to be a very enjoyable game. The same die cast used to determine the

attacker/defender role and terrain also resolved the replenishment of troops

for the battle. Unfortunately, the successive defeats by the Suevi meant repeatedly

meeting the enemy with an inferior force.

The game comfortably moved through two decades of play

taking two days to play. To reach 429 AD, 37 cards were drawn to initiate

tribal or Roman activity. Key historical events did fall into place if not by

their exact month, then certainly by their correct year.

After the death of Maximus, central authority in

Hispania disappears leaving local senators to negotiate directly with the

various tribes. The value of the card drawn (club) determined if this was

successful or not.

I am pleased with the rule set reaching a near

historical result. The Vandals and Alani did make their crossing to Africa on

time. It remains to be seen if the Suevi could create their empire in Hispania

given the weakened state of their army.

Next planned tests will bring my newly painted armies

to the table. Each of the armies will be presented with a brief history, their painting

and photos. This will give me the necessary time to design a map and write a

scenario for the third campaign.

Cheers,